Tö-pa are utilised for Vajrayana practices such as tsog’khorlo (tshogs ‘khorlo / ཚོག་འཁོར་ལོ་ / ganachakrapuja) the Tantric Feast Profferment. This is the visionary banquet which celebrates the three realised spheres of Vajra Master (presence display, personality display, and life-circumstances display) and mends breaches in damtsig (gDam tshig / གདམ་ཚིག་/ samaya).

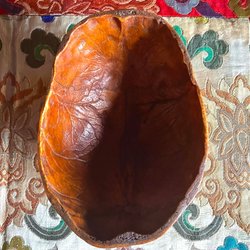

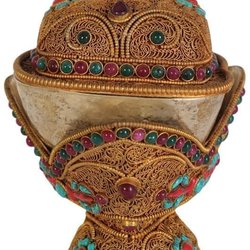

Töd-pa are made of human skulls (male and female as a pair) — but there are also smaller tö-pa which are made of metal either silver or iron. These metal tödpa are preferable for a chogtsé (Lama’s table) or for a small Trö-khang (khro khang / ཁྲོ་ཁང་) wrathful shrine.

The two skull bowls contain the Sha-nga Düd-tsi nga (sha lNga bDud rTsi lNga / ཤ་ལྔ་བདུད་རྩི་ལྔ་ ) the five ‘meats’ and the five ‘nectars’. The ‘meats’ are usually represented by any kind of meat — and the nectars by alcohol.

The five ‘meats’ and the five ‘nectars’ represent substances, comestibles, and beverages which are considered foul or disgusting.

This profferment symbolises transcendending the concept of samsara and nirvana as a mutually-exclusive polarity. It also symbolises transcendendence of the ‘pure / impure dichotomy’. These profferments are important in the Three Inner Tantras.

The five meats (shar nga – shar lNga / ཤར་ལྔ་) are: human flesh (shar chen / ཤར་ཆེན་) cow flesh (nor shar/ ནོར་ཤར་) dog flesh (khyi shar / ཁྱི་ཤར་) elephant flesh (gLang shar / ཀཉལང་ཤར་) horse flesh (rTa shar / རྟ་ཤར་).

The five nectars (Düdtsi Na-nga - bDud rTsi sNa lNga / བདུད་རྩི་) are: urine (gCin / ཧཅིན་) excrement (sKyag / སྐྱག་) blood (khrag / ཁྲག་) semen (khu / ཁུ་) pus (chu ser / ཆུ་སེར་)

Ngak’chang Rinpoche wrote:

‘The five meats and five nectars represent the overthrow of mundane religion – as a spiritualised path of social control and pedestrian mediocrity. Where religion becomes a set of laws that have to be obeyed—rather than a body of knowledge that has to be discovered—reality needs to be revealed through overturning political and spiritual correctness.

The five meats and five nectars were reviled by the Brahmanical tendencies which remained in Buddhism even though Buddhism was no longer part of the Hindu culture from which it sprang.

Apart from human flesh we can eat what we please. As for the five nectars we are free to experiment – but we have no obligation to avoid these things in terms of our societies. The five meats and five nectars were almost universally not taken literally in Tibet – they simply represented the need to go beyond codified limits.

In the West Buddhism is not encumbered by Brahmanism – but by political correctness and puritanism.

In the current atmosphere of the politicisation of ethical values—and cosseting demands for safety—originality and natural kindness are crippled. Simply partaking of meat and alcohol therefore, serves the original purpose of the five meats and five nectars.’

Khandro Déchen said

“In ancient India this profferment overturned the ‘purity-obsession’ of Brahminism — but it now has equal importance in overturning rhe tyrannical tendencies within ‘political correctness’ and ‘spiritual correctness’. Neither are function in terms of Vajrayana.

The humanitarian value of certain aspects of political correctness is not in question — simply the idea that they can override Vajrayana.”

Ngak’chang Rinpoche added. “Vajrayana cannot not be judged according to criteria which are not based on nondual realisation.”